Not sure where to start?

Try the Personal Concerns Inventory (PCI) to clarify what to focus on, or start with Relaxation Therapy for guided meditation.

Try the Personal Concerns Inventory (PCI) to clarify what to focus on, or start with Relaxation Therapy for guided meditation.

Being “in the zone” should be the rule, not the exception. A command performance – whether in the arts, athletics, or any other aspect of life – requires your total commitment. Ray Mulry’s powerful and illuminating book, In The Zone, offers a specific methodology for reaching and maintaining your highest aspirations.

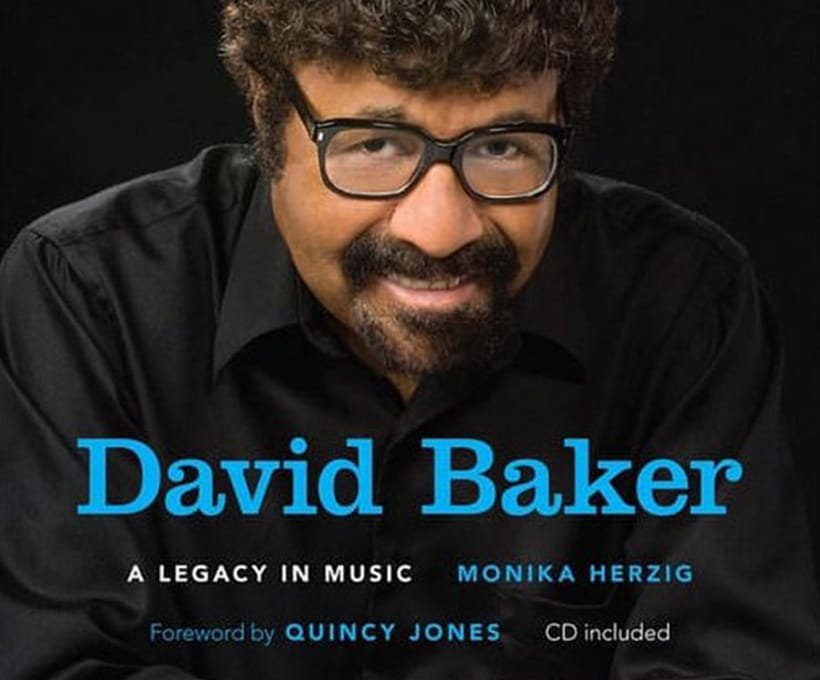

David N. Baker, Jazz Musical Director, Smithsonian Jazz Workshop Masterworks Orchestra and Distinguished Professor of Music, Indiana University

I first met David Baker in the early 1970s when we were teaching at Indiana University. We were introduced by a mutual friend, a student of David’s, thinking I might be of assistance regarding David’s injury in a car accident and the resulting complications with his speech and embouchure. He was an injured musician, and I was a young professor of clinical psychology. It’s an interesting story, never told before, and I would like to share it with you.

The following is taken from Monika Herzig’s book, David Baker, A Legend in Music:

“At the height of his career as a performer, Baker had to deal with the consequences of a tragic injury sustained in a car accident that required him to give up playing the trombone and effectively reinvent his musical career. On the drive back to Indianapolis with drummer Ray Churchman after their last night with Fred Dale’s group at Lake Hamilton Resort in Hamilton, Indiana, in the summer of 1953, Baker was asleep in the front seat. The impact of a head-on collision with another vehicle ejected him through the windshield into a cornfield, as seat belts were not a common security measure at the time. Baker suffered life-threatening injuries, including a partially severed left arm, and awoke after a week-long coma in a hospital in Huntington, Indiana. Although he recovered the use of his arm, he began having problems with speech and embouchure several years later. Doctors informed him that he had been playing with a dislocated jaw for seven years and that the injured side had atrophied as the healthy side enlarged to compensate. Throughout the late 1950’s until the end of 1960, Baker underwent multiple operations, wore acrylic braces to keep his jaw in place, and even had his jaws wired shut for weeks.”

Moniker Herzig continues, “The prospect of starting from scratch on a new instrument at the age of thirty-one was devastating and frustrating, as it would take years to achieve anything close to his facility on the trombone.”

At this time, David and I met and started our work together. From our first visit, it was clear David was compassionate when discussing the trombone. Even just mentioning the instrument caused him to experience spasms in his jaw. We met frequently and eventually found success. One afternoon, David came by my home and said, “I’ve got something for you, and suggested we go to the backyard, at which time he took out his trombone and played “Satin Doll.”

David was now able to play his chosen instrument, and as a thank you, he wrote a Jazz composition titled RAMU, published by Creative Jazz Compositions in 1972. I have never felt so honored, and I consider David’s thoughtfulness my most cherished memory. We remained friends until his passing on March 26, 2016.

For those of you interested in learning more about this most creative and brilliant “Teacher,” I submit the following by Monika Herzig:

“To David Baker, composer, teacher, conductor, leader, mentor, and friend – whose work, leadership, and friendship have touched generations of musicians and audiences around the globe.”

Monika Herzig, David Baker, A Legacy in Music, Indiana University Press with Forward by Quincy Jones, 2011 by Indiana University Press ISBN 978-0-253-35657-4